Elixir Misconceptions #1

Don't "let it crash". Let it heal.

This is the first of a series on misconceptions about Elixir. These are my opinions. I hope they spark discussion and that maybe we all learn things as a result.

A note to the Elixir programmers who commonly say “let it crash”: This phrase gives outsiders and newcomers the wrong idea, and encourages bad habits for those who misinterpret it. If I had my way, we would stop saying it.

Let it crash.

Elixir runs on the BEAM VM. If you’re familiar, skip to the next paragraph. Otherwise, some necessary context is that on the BEAM, all code is executed in a “process”. This can be thought of kind of like a green thread. Each process is a lightweight, share-nothing unit of concurrency. Processes communicate via message passing. When processes encounter an unhandled error, the process exits. We use supervisors (which are themselves supervised typically), to then restart any given crashed process.

When people say “let it crash”, they are referring to the fact that practically any exited process in your application will be subsequently restarted. Because of this, you can often be much less defensive around unexpected errors. You will see far fewer try/rescue, or matching on error states in Elixir code.

The “it” in “let it crash” to an Elixir programmer is a process. Not your application.

In practice, an Elixir application almost never crashes, even in conditions that would hard-quit in any other system.

For those without the context of building Elixir applications, “let it crash” gives the impression of “jank”, of non-elegant code that does not consider user experience or possible failure states. A panic or crash in most languages is a catastrophic event, to be avoided at all costs.

Even for Elixir developers with experience, “let it crash” as a practice loses enough nuance so as to be reductive, and I’ve seen it actively impact the quality of code that comes across my desk.

First, we’ll talk about why you shouldn’t “let it crash”, and then we’ll talk about what you should do instead.

Processes are tied to real things

Open a socket connection, receiving or sending an HTTP request, opening a file, connecting to a database: all of these things are typically backed by a process. 99% of the time, that process is linked to the process that asked for that to happen. The most straightforward example of this is in the context of a web server communicating over a web socket, and if you’re familiar with it, Phoenix LiveView.

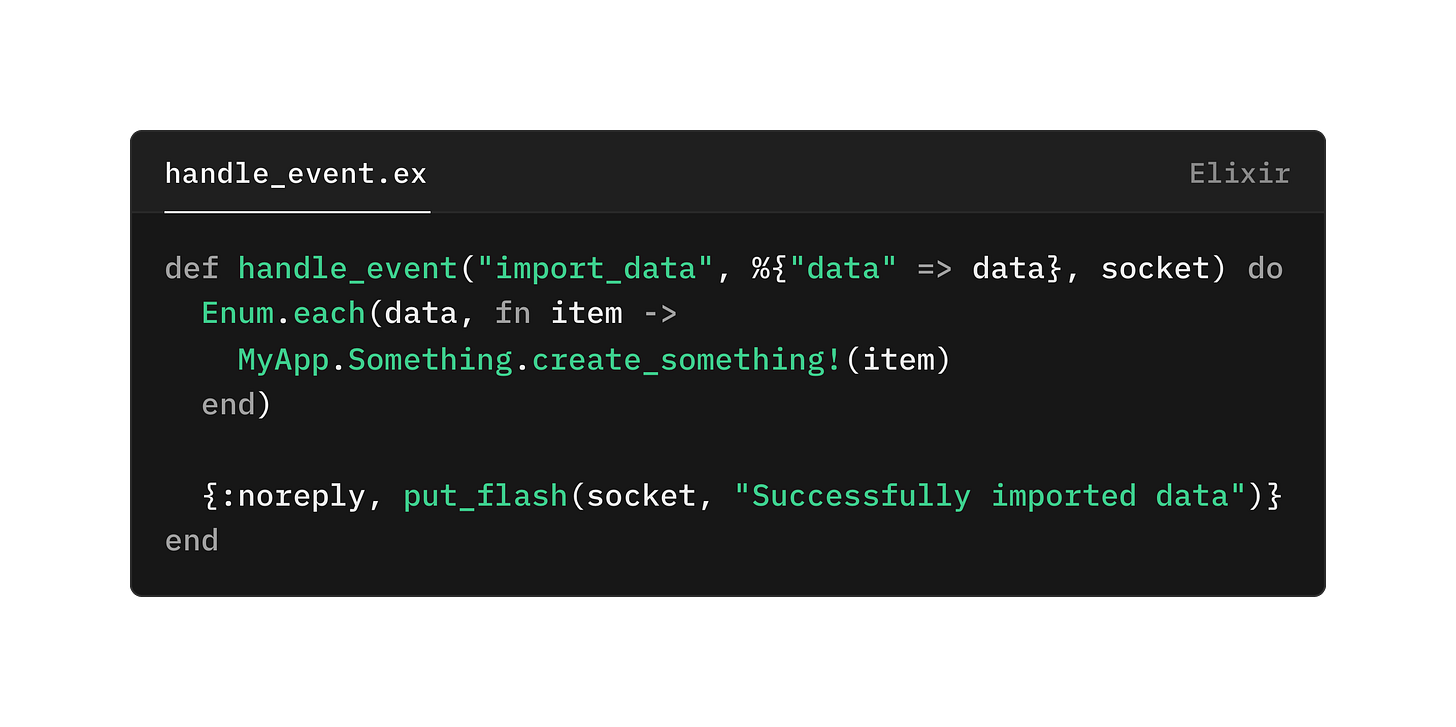

Lets imagine that we embrace the “let it crash” philosophy to the bone, and we write some code like this, handling a web socket message:

This code will crash the process in the following scenarios:

the pattern match on the event name fails `”import_data”`

the pattern match on the input params fails (there is no “data” key)

`data` is not a list (technically, an enumerable of some kind)

Any given item in data fails to be created or raises an error

In some cases, especially “invalid messages that should not be producible”, crashing is a good thing. For the first two, and maybe three things in the list above, hitting those cases implies a bug in your front end likely. Someone sending your process messages it was never designed to handle. Crashing may be the desired behavior.

BUT: There is a user on the other end of this. In the case of LiveView, the web socket is driving at least some part of their experience. Establishing a websocket takes time. What will the user experience be? Will they see a flash message about something going wrong? Will some of their UI state reset? None of these things are really acceptable. This pattern is all over, not just tied to LiveView. Do you want to close whatever file/database connection you have every time anything goes wrong? Or release some other expensive resource? What if you encounter thousands errors in quick succession? Will restarting be expensive?

Representing Failed States

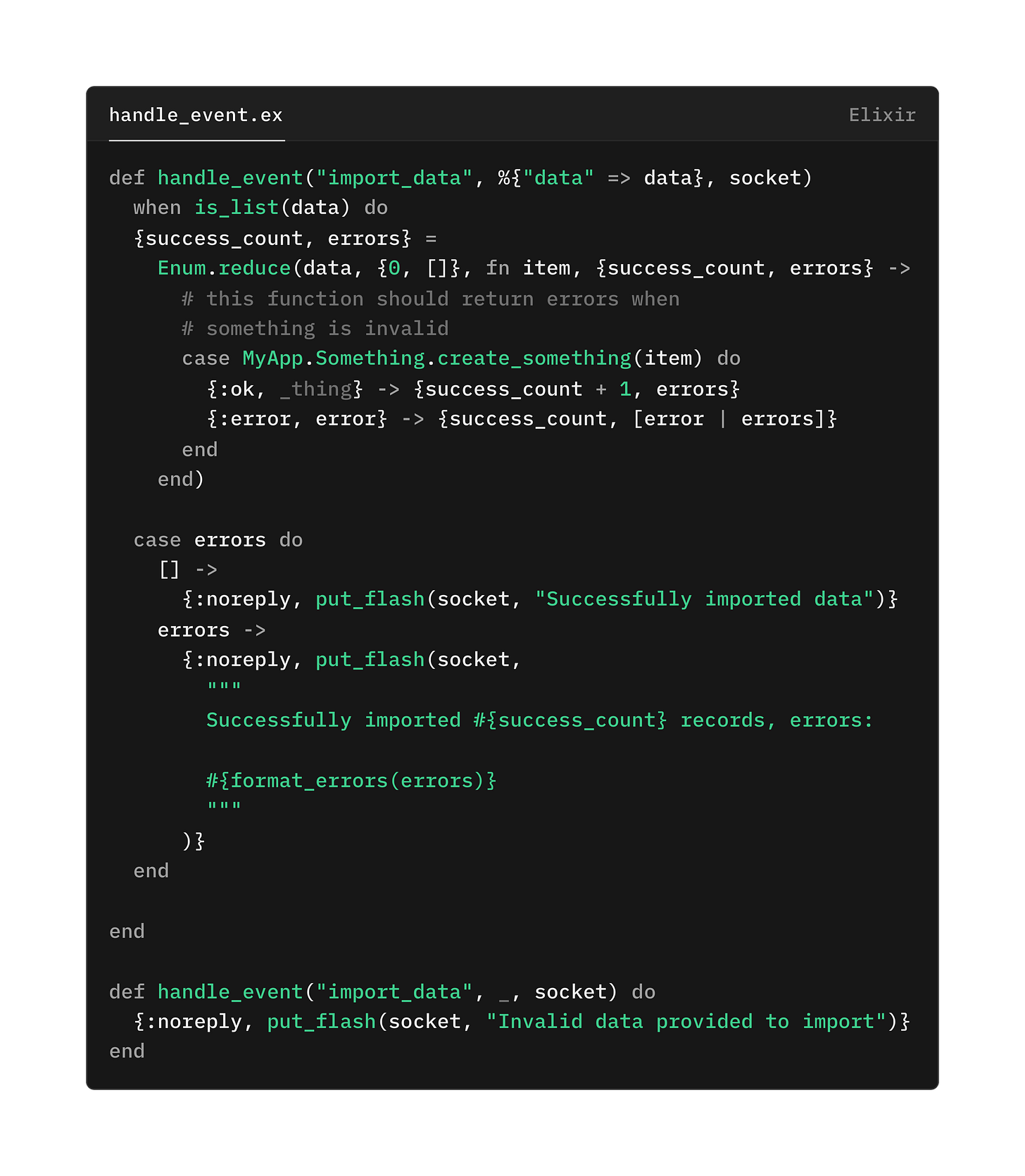

Intentionally crashing on any possible error also means that you are not able to represent errored states to your users. For our above example, something like this might make more sense:

In this example, instead of just crashing and seeing some generic error, the user is given actionable information about what went wrong. We have represented the failed state.

With that said, in practice we take a middle-way. Specifically, in fully unexpected scenarios that cannot be remediated, like getting a malformed “import_data” command, it is often preferable to crash. We crash because the process is now in an unrecoverable bad state, and we don’t know how it got there. In this case, we want to remount the component into a good state. You still have to consider the UX of this scenario, and design your pages to gracefully remount.

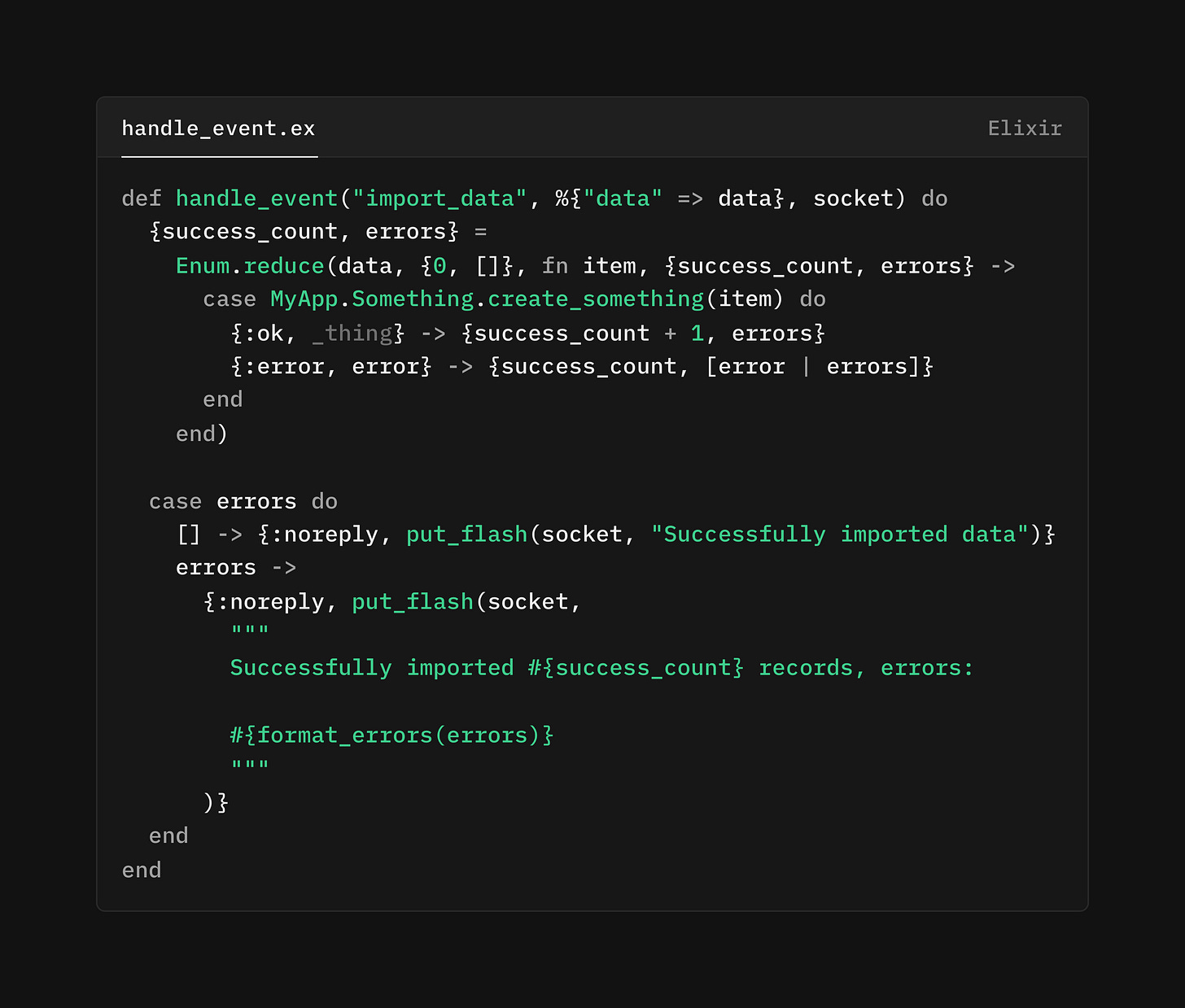

Here we crash on unknown or garbled messages/input, but present validation errors to the user.

So, we’ve established that there are consequences to crashing, and that we should not default to the overly reductive “let it crash” mentality here. Does that mean that the “let it crash” people entirely wrong? Only kind of.

Let it heal

Remember when we talked about supervisors and restarting etc? The operative part of these things is not that processes are designed to crash, it is that they are designed to start. As in, when your application first boots up, you have to start up your process tree, and supervisors are at that point embedded with the information required to start a process if it crashes.

What this means for Elixir programmers is that we can let it crash when things are unrecoverable. What this does not mean for Elixir programmers is that all errors anywhere inside of a process should cause a crash.

The real magic of the BEAM is that for any given piece of code running in Elixir, there is another, higher level piece of code that knows how to handle errors that cannot be locally handled by that code.

You can’t write code that isn’t aware of the fact that something might go catastrophically wrong, because all of your code implicitly has a “how do I initialize myself” step that must be able to gather any requirements and “set the stage” for itself.

There is often still work that goes into designing these structures, but we are getting something for free or close-to-free that takes a crack team of experts or specialized frameworks to achieve in other languages.

While “let it heal” may not be as catchy, I think it better captures the BEAM’s true superpower: not that our processes can die, but that they can always come back to life.

In a recent discussion about type-safe languages and the property that "it never crashes", I pointed out that these things run on fallible hardware and what's nicer than a system that almost never crashes is one that always recovers.

Maybe better said as "Let it recover"

I fully agree with you. I’d only add that sometimes it’s hard to decide what to handle vs what to “let heal”, so IMO that’s when error tracking tools like Honeybadger come handy: when you’re notified of an unexpected / unhandled error, you can decide if it’s something you’d want to handle or if it’s fine to let it heal.